Betsy Bird & Julie Danielson Share Reading Advice

August 6, 2014

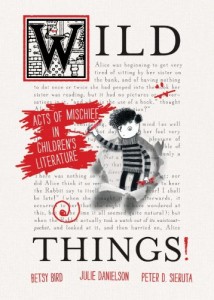

This week, New York Public Library’s Youth Materials Collections Specialist Betsy Bird and Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast blogger Julie Danielson published Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature (co-written with Peter Sieruta).

This week, New York Public Library’s Youth Materials Collections Specialist Betsy Bird and Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast blogger Julie Danielson published Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature (co-written with Peter Sieruta).

Betsy wrote a fabulous introduction to Born Reading: Bringing Up Bookworms in a Digital Age, so I caught up with the two authors to get some interactive reading advice from these children’s book experts…

Q: Betsy, you recommend A Time to Keep by Tasha Tudor as your favorite picture book as a kid. Any advice for parents reading this for the first time?

Betsy Bird: My favorite picture book as a child was a throwback to 1800s nostalgia. You know why? Cupcakes.

That woman had a way of presenting food that would rival Laura Ingalls Wilder (another author I adored almost entirely because of how she presented foodstuffs). If you’re reading it to a kid for the first time, don’t show it to anyone too young.

They’ll have to be at least 3-years-old to get the gist of it. The book goes through the months and talks about what a little girl’s mother used to do when she was young. I suspect the book is directly responsible for my own daughter demanding I tell her three stories every night about “what happened in the old days when you were a little kid”. And that, as far as I can tell, is the best way to make the book interactive. After reading it, kids might want to know what their parents were like as children.

It’s a great gateway book to showing the past, to a certain extent. Good for bonding too.

Q: Julie, you recommend Trina Schart Hyman’s illustrated version of Snow White. Any advice for parents reading this for the first time? What can they do to make the reading experience more interactive and get the kids involved in this book?

Julie Danielson: I don’t know that this is necessarily advice, but one thing I love about picture books is to sit back and soak in how illustrators extend a story (the written words, that is) and interpret a tale. And it’s fun to do that with fairy tales. You can take five different illustrated versions of Snow White and see five wildly different takes on it (in some ways, five wildly different stories), based on the illustrators’ styles.

So, to read Hyman’s Snow White and to then follow it up with, say, Nancy Ekholm Burkert’s Snow White (published two years before Hyman’s) is to see two very different stories. And to have a conversation with children about how the tales differ, based on the illustrator’s choices (same story, different art), is a powerful thing.

In fact, Perry Nodelman does this in his book Words About Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. (For fun, follow it up with Wanda Gág’s Snow White — and then do the same with Little Red Riding Hood. James Marshall’s Red Riding Hood is quite a different thing from Trina’s Red!)

Q: Betsy, what did you learn about Robert McCloskey’s ducklings that surprised you as you wrote the book? Does any particular anecdote stand out?

Betsy Bird: We recently received a review from Kirkus that said that our story about the ducklings in Make Way for Ducklings was “old news”. Still I, for one, wasn’t really aware of the details surrounding the end of their story. As many people know, the ducks in that book were based on real life duckling models that McCloskey purchased and kept in his Greenwich Village apartment (LIFE Magazine was so charmed they did an article about it at the time).

Few people are aware of how he chose to slow the ducks down (two words: red wine). And fewer still know what happened to the ducks after they finished their modelling stint. We found out and the answer is in our book but I won’t give it away for you here.

Q: Julie, what did you learn about Trina Schart Hyman and James Marshall that surprised you as you wrote the book? Does any particular anecdote stand out?

Julie Danielson: There is a wicked (in more ways than one) funny story about James Marshall’s revenge on someone who had slighted his ailing father. No one gets slayed or anything, but it’s a funny story involving alligator pumps that goes to show, as we write in the book, that the man was anything but fluffy bunny-ish.

As for Trina, well … just when you think you know every story of mischief she’s involved in, you stumble upon something new. When writing about something she slipped into an illustration, a rather macabre moment of revenge, we learned that she’d slipped something naughty (no other word for it) in yet another book. Even Peter didn’t know that story, and he knew just about everything.